Instructional Design

- Course Redesign Using Learning Theory

- How 1990s Computer Mediated Communication can inform today's MOOCs

- Theory of Practice

- Needs Assessment and Proposal Development

- Analysis and Assessment

- Instructional Materials

- Introduction to Innovation (Sample Course Notes)

Course Redesign Using Learning Theory

Introduction

Here I investigate the use of new learning technologies to adapt the materials from an existing course on "ICT Sustainability" (Worthington, 2011) to be delivered as a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC). The existing course was designed for on-line delivery to small groups of adult learners who have a university first degree and with the assistance of a tutor. The task then is to see how the same material could be used with large numbers of less advanced students, without tutor support, while retaining the ability to use the same materials in a tutor lead small online course. The current course uses a constructivist approach to education, derived from that of the UK Open University (Lindley, 2008). It is proposed to supplement this with the Personalised System of Instruction (PSI), developed by Keller (1974). This hybrid mode (Neo & Neo, 2010) would provide more support in learning the basic elements in a MOOC version of the course for less advanced students. The major issue with the use of PSI is not the efficacy of the technique, which already in use for vocational education in Australia, but in making it acceptable to university academics. It is proposed to do this by using PSI as a supplement to the existing constructivist approach.

Background

In its flexible learning strategy, the University of British Colombia identified three issues for universities (UBC, 2014):

-

Increasing focus on vocational education,

-

Online competition,

-

Demand for mid-career education.

The problem for higher education institutions is to provide courses which are accessible (preferably online), meet the vocational needs of students, but are also academically sound. In announcing the decision of Central Queensland University (CQU) to discontinue the use of multiple choice questions in examinations, Pro Vice-Chancellor, Professor Rob Reed, discussed the history of educational psychologist Frederick Kelly's use of the tests in WW1 US Army intelligence testing (Reed, 2014). CQU was concerned that multiple choice questions were not suitable for assessing real world skills.

Anderson and Dron (2013) categorised three generations of distance education pedagogy based on the learning theories underlying them. However while being an improvement on an analysis simply based on the technology used, this still assumes that only one approach to learning can (and should) be applied in a course (or program). Students need to have a basic knowledge of a topic, before learning advanced skills. Rather than adopt one teaching and assessment approach for a whole course, these should suit the particular material and level. It is proposed that a combination of techniques can be used to teach basic and advanced material to the same students using the same learning technology.

Origins of the Green Computing Course

In 2008 the Australian Computer Society (ACS) commissioned a course on "Green Computing" for its Computer Professional Education Program (Worthington, 2012a). The course teaches how to evaluate the carbon footprint and e-waste from IT in an organisation and recommend how to reduce them. These objectives are aligned with "Sustainability assessment" and "Sustainability strategy" from the Skills Framework for the Information Age (SFIA, 2011).

The Green Computing course is one of a series of 12 week postgraduate online courses, using a constructivist approach to education, derived from that of the UK Open University (Lindley, 2008). The course was first run by the ACS in February 2009 as "Green ICT Strategies", then adapted for the Australian National University from July 2009 as "COMP7310" and for Athabasca University as "COMP 635". The course is delivered on-line, with an e-book of course materials which is also available as a printed booklet (Worthington, 2011), group activities and assessment is via the Moodle Learning Management System.

Need for Enhancement

While well received by students, the course is resource intensive, requiring a trained tutor for each small group of students (typically six to twenty-four). Also the course is designed for a standard twelve week university face-to-face semesters, which may be too long for online study.

The Green Computing course was originally intended for university qualified IT professionals, but has also been taken by those from other professions and by undergraduates. However, it is not clear how the educational techniques developed for a cohort of postgraduate students with the same professional background will translate to a more general audience. Apart from not having the particular subject knowledge of ICT professionals, students may not have the maturity assumed by the current course design. The intention therefore is to look available learning research and theory to see what can be applied in this situation for "best practice".

The Students

The original ACS "Green Computing" course was commissioned for Australian ICT professionals as part of the ACS Computer Professional Education Program (CPEP). These students are typically adults with a degree in computing and at least two years experience working in a computing job. Almost all ACS students are Australians resident in Australia, but a few are international students resident in islands of the Pacific region. Students are typically aiming for advancement in their career by broadening their technical skills into the management area. Students are aiming to obtain postgraduate qualifications, with the CPEP being accepted for articulation into masters programs at eleven Australian universities (ACS, 2012).

In contrast to the CPEP program, ANU students undertaking the green computing course are a mix of Australian and international students, with computing degrees, some with no work experience. The students are required to be English speakers, with those having English as a second language required to pass a university level academic English test.

What most students of the green computing course have had in common has been an undergraduate degree in computing. This contrasts to the typical MOOC, with no formal entry requirements, aimed at high school graduates. Can an advanced postgraduate course for IT specialists be converted to this format?

Not all the students for the ICT Sustainability course are IT specialists, some students with engineering, environmental science, law and arts degrees have also undertaken the course. One undergraduate was able to complete the course in an accelerated four week programs (one third the normal time). A shorter two week version of the course was prepared as a student project (Worthington, 2012b). This has been used live in a classroom for high-school IT students and also adapted as an experimental edX course (Wu, 2014). This suggests the content of the course could be suitable for non-specialist students.

Proponents of MOOCs have argued that they are a way for those without formal education in developing nations to access higher education. However, research indicates that the largest proportion of students are from developed nations and already have tertiary qualifications. Nesterko et al (2013) report that developed nations accounted for 42.29% of of enrollments in HarvardX courses (as of September 8, 2013), with India having the next highest being India (9.47%). DeBoer, Stump, Seaton and Breslow (2013) report a similar distribution of students for the first edX course, MIT's "6.002x: Circuits and Electronics.", with 70.94% of students having a higher education degree. Of the students without a higher education degree, 26.68% had completed secondary school. The ANU explicitly aimed its Astrophysics Xseries Certificate, including the "Greatest Unsolved Mysteries of the Universe" edX course, at students with a high-school level education Maths and Physics (ANU, 2014). Aiming the ICT Sustainability course at a similar academic level would be appropriate. However, an issue which needs more consideration is the maturity of the students and their access to relevant information.

The Course Content

This study focuses on the teaching methods to be used and assumes the course content is appropriate and up to date. The material is checked each time the course is run (annually) and last had a major revision in 2011,being restructured to incorporate the SFIA Skills definitions (SFIA, 2011). Issues to be considered are the use of video, forms of feedback, student interaction and assessment.

As with traditional distance education courses, ICT Sustainability is heavily reliant on text based materials. The ebook is the equivalent of 100 pages of text, with no graphics. There are no video presentations accompanying the course. There are four videos from external sources recommended for the students to watch:

-

Professor Ross Garnaut discusses the challenges of climate change (pt1). 9 Minutes (ANU, 2009).

-

General EPEAT Orientation. 56 Minutes (EPEAT, 2012).

-

Google container data center tour. 7 Minutes (Google, 2010). Available:

-

Green Planet. 9 Minutes (TelecomTV, 2009).

This is eighty-one minutes of video in total, or about seven minutes per week. However, none of these videos feature the course designer and so may lack the human touch advocated by some learning theories. Friedlander and Taylor provided weekly video feedback for their Understanding India edX course to provide a more personal touch (ANU, 2014b).

Learning Theory Applied in The Current Course

Lindley (2008) described in detail the educational thinking behind the CPEP program, of which the Green Computing course forms a part. So before proposing new teaching methods, it would be useful to review those origins. The Computer Professional Education Program (CPEP) was established by the Australian Computer Society (ACS) for post university professional development. CPEP students are required to have an ICT degree and 18 months work experience in a relevant job. The aim is to foster professionalism, with graduates required to then complete at 30 hours of continuing professional development. Implicit in this is a view of the student becoming an expert and also taking responsibility for their own education.

Lindley (2008) references the Knowles' theory of Andragogy or "self-directed learning" (Knowles, 1980). However, while Knowles makes mention of Computer Assisted Instruction, this was as a form of Programmed Instruction, very far from the idea of self-directed learning: "The very notion of terminal behavioural objectives is discordant with the concept of continuing self-development toward one's full potential." (Knowles, 1980, p. 135).

The Conscious Competence Learning Model, is also applied in the CPEP with students being encouraged to reach the fourth stage of competence: "conscious competence" (Chapman, 2003?).

This concept of "conscious competence" relates closely to the use of e-portfolios and student reflection. Alongside course based subjects CPEP students are required to undertake "Professional Practice", keeping a "Reflective journal" with weekly reflections on their learning to be discussed with a mentor and prepare an ePortfolio with skill assessment and career plan (ACS, 2012b). The hope is that the student will maintain the eportfolio for used for personal development and career advancement, after the completion of the program.

The concept of "competence" is important in the area of professional development. Wilcox and King, J. (2014) explore the relationship between competencies, skills and knowledge. Lindley (2008) explicitly references Salmon's five stage model of online learning: Access and Motivation, Online Socialisation, Information Exchange, Knowledge Construction, and Construction (Salmon, 2004). However, it is not clear how these stages relate to "competence". In a later work Salmon, Gregory, Dona, and Ross (2014) report successfully using the five stages explicitly in an experiential online development course for educators. However, the researchers admit that their cohort of students were pre-disposed to this approach have been self selected due to familiarity with Salmon's approach to e-learning.

Lindley (2008, p.5) briefly mentions Outcomes Based Education (OBE), but only two of the four principles which Killen, (2000) sets down: "clarity of focus" and "designing back" (the "desired end result" of the education). Lindley does not mention Killen's other two OBE principles: "high expectations" and "expanded opportunities". Killen was writing in the context of school and vocational education and it is not clear how well OBE translates to HE, although Castillo (2014, p. 176) reviews the implementation of OBE for higher education in the Philippines, as part of a "a shift from a teaching- or instruction-centered paradigm in higher education to one that is learner- or student-centered, within a lifelong learning framework." One reason given for this is international recognition of qualifications (the example of engineering is given), so graduates can be employed in other countries, placing it in a vocational context.

Most important to the CPEP program, according to Lindley (2008, p. 6) is reflective learning. Students are required to write about their experience of learning in the program in a journal. The claim is that students will continue this practice beyond their formal learning to help with future professional development. Also it is claimed that this suits adult learners engaged in intellectually demanding activities (Hinett & Varnava, 2002).

Applying Behavioural and Cognitive Learning Theory To The Course

It might seem a step backwards to take a course designed along constructivist principles and attempt to apply Behavioural and Cognitive learning theory. However, it is suggested that a hybrid-mode learning environment (Neo & Neo, 2010) could be used, with the behavioural and cognitive techniques applied to small tasks in learning fundamentals, within a borderer constructivist approach. Behavioural theory's emphasis on measurement and observation fits well with the subject matter of ICT Sustainability, with formulas and calculations to be learned. Personalised System of Instruction (PSI) can be implemented using Learning Management System (LMS) such as Moodle, as the modern successor to Computer Based Training systems of the 1960s. While modern LMS, such as Moodle are usually promoted as supporting a constructivist or social constructionist approach to education, they have the facilities to support older approaches.

Shafeeq and Rahman (2014) point out that the influential early PLATO system (Programmed Logic/Learning for Automated Teaching Operations), developed in 1959 by the University of Illinois, used a Behaviourist approach to learning. This "drill-and-practice" approach providing the student with feedback on their progress and matching the learner's pace are still applicable for basic learning tasks.

As an example of a basic task in the green computing course, the computation of carbon emissions from electricity use by computer equipment could be taught with a simple computer based application. The system would present the formula and explanation from the current course notes, with students being asked multiple choice questions to assess their comprehension. Common misconceptions would be detected and additional material provided. The student would be presented with worked examples of formulas, possibly using illustrations (perhaps even animated illustrations) and the student asked "fill in the blank questions".

Personalised System of Instruction Applied to Higher Education

Keller's Personalised System of Instruction (PSI), was developed in the mid 1960s for teaching physiology (Keller, 1974). The elements which Keller described for his system are:

-

Utilising of course content,

-

Self pacing of the student through the units,

-

Mastery demanded at each step,

-

Repeated tests without penalty and maximum credit when done,

-

Proctors, to assist the students.

By 1974 Keller reported that this approach was being used for 412 courses, including ones in engineering and mathematics/statistics (Keller, 1974). Keller also reported the use of PSI at secondary schools and for postgraduate level. Also he pointed out that proctors were not strictly necessary, if teachers can relate to the student's experience). While it might seem a little old fashioned, this can be used with modern Learning Management Systems for the basic parts of a course.

Smith (2010) describes the competency-based training (CBT) approach of Australia's Vocational Education and Training (VET) system as "competency-based curriculum". Harris and Schutte (1985), make the link between TAFE education (TAFE being the earlier term for VET), competency and the Keeler Plan:

"Competency-based education may most appropriately be described as a synthesis of two other well known alternative educational systems: Mastery Learning and Keller's Personalised System of Instruction." From: Harris and Schutte (1985, p. 52).

PSI can be seen as an elaboration of Skinner's Programmed Instruction. The idea of changing the behaviour of students using a teaching machine is a concept not well accepted for university education and not helped by Skinner's examples of teaching pigeons to perform (Skinner, 1954). It is more accepted in VET vocational education, particularly as one of the aims of such education is to change the behaviour of students so they conform to workplace requirements.

There are clear parallels between PSI's seven elements and the approach to training by Australia's VET Registered Training Organisations. Nationally standardised training packages are made up of units of competency, with students required to pass each unit. Students will typically work in a workshop with an instructor present to help and undertake computer based modules in a learning centre with a roving proctor, or online at home (with online assistance). Students are not given a grade, but just considered "not yet competent" until "competent". Smith describes this form of assessment somewhat dismissively as "Tick and flick" (2010).

The use of a PSI approach is not widely accepted in Australian Higher Education outside the VET sector. While VET has a nationally standardised database of training packages and modules with competency based assessment, Australian universities each develop their own courses, which are not divided into standardised modules and not each competency assessed. University academics are unlikely to accept a wholesale change to the VET approach, but it is suggested may accept incorporation of some of its features within courses. Forsyth (2014, p. 191) questions the packaging of on-line courses into "chunks" and the conversion of students into consumers of education as a commodity. Kazi (2004) questions if such courses are achieving their pedagogical goals, or being used just because they are easy to track student progress. However, carefully structured materials which provide re-enforcement through small tests could be seen as a useful part of an overall program.

Use of VET Educational Materials

The use of VET educational techniques for a university course suggests that the VET sector should be looked at as a source of educational materials. A search of the Australian National Register on Vocational Education and Training (Australian Department of Industry, 2013) found a Vocational Graduate Certificate in Information Technology Sustainability (ICA70211). Of the twelve units of competency for this qualification, five relate directly to sustainability:

-

ICASUS702A - Conduct a business case study for integrating sustainability in IT planning and design projects

-

ICTSUS7235A - Use ICT to improve sustainability outcomes

-

ICTSUS7236A - Manage improvements in ICT sustainability

-

ICTSUS8237A - Lead applied research in ICT sustainability

-

ICTSUS8238A - Conduct and manage a life cycle assessment for sustainability

However, use of these units of competency would require extensive reworking of the course materials. Also the vocational nature of some material is not as applicable, for example "Install and test power saving hardware" (ICTSUS4184A) is intended for training technicians who are licensed install equipment. It is not clear if the VET material can be easily converted for university use. An alternative approach which applies PSI to the existing course content to ensure mastery of the basic concepts, along with the existing assessment process for higher level concepts seems most appropriate.

Recommendations

-

Retain existing course content structure: The course is currently divided into twelve weekly modules, each comprising eight to ten hours work for a student. This structure should be retained.

-

Divide Modules Into Smaller Components Using Keller's PSI: The content within each week should be broken into smaller components using Self pacing, Mastery and Repeated tests.

-

Add Quiz Based Assessment: The current weekly assessment which uses free form answers to questions should be supplemented by the quiz questions of the Repeated tests, to provide students with feedback on their progress with basic material. This should replace half the weekly assessment. Students would receive a mark of 1 for this and not be permitted to proceed until they have achieved that mark.

-

Retain discussion forums: The current discussion forums would be retained, but just one question would be asked each week in each topic (instead of the current two or three). The material not covered in questions would be included in the quiz based assessment.

-

Peer assessment of forum contributions: The discussion forum contributions of students would be peer assessed.

-

Retain Assignment Based Assessment: The current two assignments for the majority of assessment would be retained, along with assessment by an expert human tutor. This component of the course would not be available for the free/low cost MOOC version of the course.

References

ACS, (2012a). ACS CPEP Articulation Pathways. retrieved October 1 2014, from Australian Computer Society Web Site: http://www.acs.org.au/professional-development/cpe-program/pathways

ACS, (2012b). Professional Practice Online Course. retrieved October 2 2014, from Australian Computer Society Web Site: http://www.acs.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/12385/18_ACS_Fact-sheet-professional_practice.pdf

Anderson, T., & Dron, J. (2013). Três gerações de pedagogia de educação a distância. EAD em FOCO, 2(1). URL: http://eademfoco.cecierj.edu.br/index.php/Revista/article/viewArticle/162

ANU, (2009). Professor Ross Garnaut discusses the challenges of climate change (pt1). (Video). Australian National University. URL: http://www.anu.edu.au/vision/videos/4281/

ANU, (2014a). Greatest Unsolved Mysteries of the Universe. retrieved October 1 2014, from edX Web Site: https://www.edx.org/course/anux/anux-anu-astro2x-exoplanets-1443

ANU, (2014b). Engaging India. retrieved October 1 2014, from edX Web Site: https://www.edx.org/course/anux/anux-anu-india1x-engaging-india-1376

Australian Department of Industry, (2013). About training.gov.au. retrieved October 9 2014, from National Register on Vocational Education and Training (VET) in Australia Web Site: http://training.gov.au/Home/About

DeBoer, J., Stump, G. S., Seaton, D., & Breslow, L. (2013). Diversity in MOOC students' backgrounds and behaviors in relationship to performance in 6.002 x. In Proceedings of the Sixth Learning International Networks Consortium Conference. URL http://tll.mit.edu/sites/default/files/library/LINC%20%2713.pdf

Castillo, R. C. (2014). A Paradigm Shift to Outcomes-Based Higher Education: Policies, Principles and Preparations. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research (IJSBAR), 14(1), 174-186. URL http://gssrr.org/index.php?journal=JournalOfBasicAndApplied&page=article&op=download&path%5B%5D=1809&path%5B%5D=1607

Chapman, A (2003?). conscious competence learning model. retrieved October 5 2014, from businessballs.com Web Site: http://www.businessballs.com/consciouscompetencelearningmodel.htm

Claros, I., Garmendia, A., Echeverria, L., & Cobos, R. (2014, April). Towards a collaborative pedagogical model in MOOCs. In Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), 2014 IEEE (pp. 905-911). IEEE. DOI 10.1109/EDUCON.2014.6826204

EPEAT, (2012). General EPEAT Orientation. (Video). Green Electronics Council. URL: http://www.screencast.com/t/J9BxlLpX

Forsyth, Hannah (2014). A history of the modern Australian university. Sydney, N.S.W. NewSouth Publishing

Google, (2010). Google container data center tour. URL http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zRwPSFpLX8I.

Harris, R., & Schutte, R. (1985). A Review of Competency Based Education. Issues in TAFE. CE 043 171, 43. URL http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED265295.pdf#page=5

Hinett, K., & Varnava, T. (2002). Developing reflective practice in legal education (p. 51). Coventry: UK Centre for Legal Education. http://78.158.56.101/archive/law/files/downloads/664/878.2de9ed48.developingreflectivepracticeKarenHinett.pdf

Kazi, S. A. (2004, September). A conceptual framework for web-based intelligent learning environments using SCORM-2004. In Advanced Learning Technologies, 2004. Proceedings. IEEE International Conference on (pp. 12-15). IEEE. DOI 10.1109/ICALT.2004.1357365

Keller, F. S. (1974). Ten years of personalized instruction. Teaching of Psychology, 1(1), 4-9. URL http://www.library.unh.edu/special/forms/keller/ten%20years.pdf#page=2

Killen, R. (2000). Outcomes-based education: Principles and possibilities. Unpublished manuscript. University of Newcastle, Faculty of Education. URL http://drjj.uitm.edu.my/DRJJ/OBE%20FSG%20Dec07/2-Killen_paper_good-%20kena%20baca.pdf

Knowles, Malcolm S. (Malcolm Shepherd) (1980). The modern practice of adult education : from pedagogy to andragogy (rev. and updated). Association Press ; Chicago : Follett Pub. Co, [Wilton, Conn.]

Lindley, D. (2008). A research proposal to assess the efficacy of initial professional development offered by professional associations, in particular, the Computer Professional Education Program offered by the Australian Computer Society. In Proceedings of the Adult Learning Australia 48th Annual National Conference, November, Fremantle Western Australia. URL https://ala.asn.au/images/document/ALA_Paper_David_Lindley.pdf

Neo TK, K., & Neo, M. (2010). Interactive multimedia education: Using Authorware as an instructional tool to enhance teaching and learning in the Malaysian classroom. Digital Education Review, (5), 80-94. URL http://greav.ub.edu/DER/index.php/der/article/viewFile/56/144

Nesterko, S. O., Dotsenko, S., Han, Q., Seaton, D., Reich, J., Chuang, I., & Ho, A. D. (2013). Evaluating the geographic data in moocs. In Neural Information Processing Systems. URL http://nesterko.com/files/papers/nips2013-nesterko.pdf

Nyoni, J. (2014). Self-Regulatory Learning Behaviours in Open and Distance Learning: Priming Appropriate Online Mediation Contexts for Multicultural Students. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(15), 441. URL http://www.mcser.org/journal/index.php/mjss/article/download/3251/3205

Reed, R (2014, September, 19). Does the student a) know the answer, or are they b) guessing?. retrieved October 8 2014, from The Conversation Web Site: https://theconversation.com/does-the-student-a-know-the-answer-or-are-they-b-guessing-31893

Salmon, Gilly (2004). E-moderating : the key to teaching and learning online (2nd ed). RoutledgeFalmer, London

Salmon, G., Gregory, J., Dona, K. L., & Ross, B. Experiential online development for educators: The example of the Carpe Diem MOOC. URL http://publicservicesalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/www.gillysalmon.com-uplo...t_pre_peer-reviewed.pdf

SFIA Foundation, (2011). Skills Framework for the Information Age, Framework Reference Version 4. retrieved September 30 2014, from SFIA Foundation Web Site: http://www.qgcio.qld.gov.au/images/documents/QGEA_documents/govnet/Documents/Projects%20and%20services/ICT%20workforce%20capability/SFIA%20v5%20-%20framework%20reference.pdf

Shafeeq, C. P., & ur Rahman, M. M. (2014). An Outline of Developments in Language Learning Technologies. URL http://www.iairs.org/PAPERS/PAGE%2051%20-%2054.pdf

Skinner, B. F. (1954). The science of learning and the art of teaching. Cambridge, Mass, USA, 99-113

Smith, E. (2010), A review of twenty years of competency-based training in the Australian vocational education and training system. International Journal of Training and Development, 14: 54-64. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2419.2009.00340.x URL: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-2419.2009.00340.x/full

TelecomTV, (2009). Green Planet. (video). URL http://www.mobileworldlive.com/green-planet-episode-1-the-green-economy.

UBC, (2014, September, 15). Flexible Learning: Charting a Strategic Vision for UBC (Vancouver Campus) FOR UBC. retrieved October 8 2014, from University of British Columbia Web Site: http://flexible.learning.ubc.ca/files/2014/09/FL-Strategy-September-2014.pdf

Wilcox, Y., & King, J. (2014). A Professional Grounding and History of the Development and Formal Use of Evaluator Competencies. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 28(3). URL http://cjpe.journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/cjpe/index.php/cjpe/article/download/170/pdf

Worthington, Tom (2011). ICT sustainability : assessment and strategies for a low carbon future. Tomw Communications, Belconnen, A.C.T URL http://www.tomw.net.au/ict_sustainability/

Worthington, T. (2012a). A Green computing professional education course online: Designing and delivering a course in ICT sustainability using Internet and eBooks. 2012 7Th International Conference On Computer Science & Education (ICCSE), (Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Science and Education, ICCSE 2012) 263. doi:10.1109/ICCSE.2012.6295070

Worthington, T (2012b). How Green is My Computer?. retrieved September 30 2014, from Tomw Communications Pty Ltd Web Site: http://www.tomw.net.au/How_Green_is_My_Computer/

Wu, H (2014). ICT Sustainability. retrieved September 30 2014, from ANU edX Edge Web Site: https://edge.edx.org/courses/ANUHonsProject/COMP7310/2014_T2/about

How 1990s Computer Mediated Communication can inform today's MOOCs

Introduction

This review looks at one study from the late 1990s into what the range of participation in CMCs was and why (Taylor, 1998). This could be useful in informing today's e-Learning and MOOC developers. The use of Computer Mediated Communication (CMC) for education is now the subject of discussion in the media. Many reports on the use of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), make claims that students will engage with computers for education in a new way. However, there are decades of literature on computer based distance education which can inform the current debate. MOOCs have been proposed as a way to broaden access to education, but have barriers to previous forms of online participator been overcome?

The Research Process

Taylor follows a conventional research process, starting with a literature review (Taylor, 1998, p. 13) looking at previous studies of the interaction of students and instructors (interestingly Taylor changes from "instructors" to use the term "moderators" later). Most papers referenced are from the early to mid 1990s, during the early days of the use of the Internet. As a result Taylor emphasises the limitations of the media at the time. This remains an issue today, particularly for developing nations and in regional and remote areas, with limited Internet access. Some of the pre-Internet studies Taylor discusses are also still relevant, as they concern the educational effectiveness of the use of two-way audio and video. While the technology used for audio and video has changed from analogue phone lines and satellite, to digital fibre optic cables, the educational outcomes are unchanged.

Taylor goes on to chart the development of Computer Medicated Communication (CMC), at this stage a purely text based media and ends with the question: "... why the learners do not seize the opportunity that is offered by CMC" (1998, p. 25). This is the central research question for the study.

Theory: Taylor's study is theory driven. The idea of interaction being of value for learning is explored and the limits of that interaction in distance education. The key theory used is Feenberg's 'phatic' expressions: non-verbal cues which are lacking from text based communication (1989). Taylor then theorises that this lack of non-verbal cues in CMC will be heightened for students who already have a fear of communicating. The student's fear of communication can be measured with McCroskey's communication apprehension (CA) questionnaire (1981) and then compared with the student's perceived and actual communication in real e-learning courses.

Statement of the Problem

Question: Taylor (1998) sets out to find why some learners participated more than others in CMCs. The study considers if a lack of participation by some students (so called "lurkers") is due to an absence of visual clues missing in text based forums or if a perceived need for high quality academic writing is deterring students.

Three research questions are asked:

-

"To what do students attribute their levels of participation in computer conferencing?" (Taylor, 1998, p. 82)

-

"Is there a systematic relationship between oral communication apprehension and levels of computer conference participation?" (Taylor, 1998, p. 84)

-

"Is there a significant difference between responses of the lurker and the non-lurker to the PRCA-24 and the computer conference participation questionnaires?" (Taylor, 1998, p. 86)

Purpose and Method: Taylor describes their study as "... an exploratory examination of the phenomenon of lurking ..." and later use the terms "explanation" and "description" for their case study to "gather basic information" (p. 36). So could best be described as exploratory basic research.

A set of definitions are provided (Taylor, 1998, p. 37) for the main concepts:

-

Lurking: a low participation rate in CMCs. This is defined for the study, as at most, two postings per conference topic of at most 150 words total. It is not clear how these values for lurking were derived, with no sensitivity analysis of them in the paper, nor sources cited.

-

Communication Apprehension: Taylor (1998, p. 29) quotes McCroskey's 1977 definition of CA as "... an individual's level of fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons." This is cited by Taylor as being originally from McCroskey's 1981 paper, but is actually from a previous study (1977). McCroskey's "Personal Report of Communication Apprehension" (PRCA-24) questionnaire is used to measure apprehension (Taylor, 1998, p. 11). The PRCA has been widely used in studies of students in North America and Australia (McDowell, 1994) and is suitable for this research.

It might be argued that Lurking and Communication Apprehension are obsolete concepts in the age of social media and smart phones, with every one (or at least every young university student) comfortable being online, all the time. However, students of any age can still experience anxiety speaking in a formal academic setting, be it online or a physical classroom, so these are issues still worth exploring.

One aspect not fully explored by Taylor (1998) is the extent to which students who are Lurking may still be engaged in the course. A student who is not originating text messages, due to Communication Apprehension may still be reading messages (that is Lurking), or may be completely non-engaged in the course, neither reading nor writing. Course Management Systems (such as Moodle) allow for the monitoring of what content the student accessed in a course, even when they did not contribute, but Taylor does not appear to have made use of this information. This may be because Taylor's approach draws heavily on McCroskey's earlier studies, at which time good "analytics" would not have been available from the early computer systems in use.

Research Design

The single case study is described by Taylor as "... non-experimental as it does not include any manipulation or control, is inductive, and does not seek to predict." (1998, p.36). However, the purpose of the study is to see if the student's apprehension about communication relates to their participation in computer conferences and this implies a causal relationship (apprehension causing lower participation). If such a relationship was found, it could be used to devise interventions to assist students at risk of under participation

Unit of analysis: Subjects of the study were 274 Athabasca University Masters of Distance Education students, studying by distance education in the first three courses of the program. These were adult students with an average of 42 years (making them different to the typical non-DE student). Taylor commented the students were "... broadly dispersed geographic locations throughout Canada" (1998, p. 38).

Sampling techniques: No sampling was used, with all students invited to take part in the study. One possible source of bias might be that students who have Communication Apprehension may be reluctant to participate in such a study and so be under-represented. A possible indication of this is that Taylor found that 60.8% of the total non-respondents to the survey met the definition of lurking, compared with only 30.7% for respondents (1998, p.69). That is, those who did not take part in the survey were about twice as likely to contribute minimally to the conferences as those who did take part.

Measurement Techniques: Two questionnaires were used, one for Computer Conference Participation and one for Communication Apprehension. The "Computer Conference Participation Survey" (Taylor, 1998, p. 89) had 31 items, using mostly a 5-point Likert scale (quantitative) and some free test questions (qualitative). This questionnaire asked about the student's experience with CMC, other factors which might effect their participation and how much they participated. The second questionnaire was the Personal Report of Communication Apprehension (PRCA-24), using a 24 item Likert scale (Taylor, 1998, p. 111), as discussed previously. In addition students were asked for permission (Taylor, 1998, p. 114) for the researchers to access the CMC to measure the frequency (postings per unit) and magnitude (words per posting) for each student participating in the study.

The study surveyed students enrolled in courses for the September to December 1995 and September to December 1996 terms. Students who withdrew within the first 30 days of the course under the university's early withdrawal policy were excluded from the analysis, as they would not then participate in the CMC. However, as a result 28 of the students (about 10%) were excluded. It is not clear why this was done, as these students may well be withdrawing due to Communication Apprehension and their exclusion would thus underestimate the effect. This methodology could not be used for Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), where the number of students renaming active in a course drops rapidly in the first few weeks. The first edX MOOC had only 50% of the students engaged after the first week (Breslow, Pritchard, DeBoer, Stump & Seaton, 2013). Even a course with highly motivated students, such as those who want to learn academic English to enrol in College (so presumably less susceptible to Communication Apprehension), showed only a 6% completion rate (Whitmer, Schiorring & James, 2014).

Findings by Talyor

The results of the Conference Activity and Experiences questionnaire show that most students reported reading the conference forums "Every couple of days" (42.30%) or "Daily" (40.38%) (Taylor, 1998, p. 48). This is consistent with a similar study of students at Open University UK, Baxter and Haycock (2014), which found that 38.1% of students were "occasional posters".

The Personal Report of Communication Apprehension - 24 Scores (Taylor, 1998, p. 62) for all students had a mean of 52.02 Standard Deviation of 17.76, which is reasonably close to compared to 65.60 and Standard Deviation of 15.30 report by McCroskey for over 40,000 college students (McCroskey, n.d.).

The data was grouped by lurker and non-lurker groups for some analysis. No weightings or adjustments were applied to the data. The data was reported in a comprehensive set of 28 tables. However, no graphs or diagrams were provided and the lack of these may have made the data more difficult to interpret for the reader.

The analysis makes use of simple statistical measures of mean, standard deviation, correlation and Chi-square test, appropriate to the quantitative data. However, the analysis carried out on two open ended text questions in the questionnaire is less clear. The responses are described as having been "tabulated" and "clustered according to any central themes that emerged" (Taylor, 1998, p. 66), however the methodology is not further described. This contrasts for example, with Carroll, Diaz, Meiklejohn, Newcomb and Adkins (2013) who describe using a thematic analysis, followed by axial coding to analyse student developed Wikis.

The PRCA-24 Scores did not show a statistically significant correlation (at a 95% confidence level) with Lurking or with Conference Participation. When divided into lurker and non-lurker groups a Chi-square test did not find a significant difference in PRCA-24 score and computer conference participation. One positive result was that participants were self aware of their level of participation, with 50% of the lurkers reporting their viewed their level of participation as at best "below average".

Discussion

While Taylor's study is now sixteen years old (1998) the discussion of the role of interaction in distance education is still relevant today. While Internet speeds have increased and more interactive software is available, the text-only nature of CMCs remains a common feature of online courses. In 2014, text based forums appear to still be the primary mode used by these successors to these courses at Athabasca University (2014). More generally, the interactive component of on-line courses may be decreasing, with MOOCs popularising pre-recorded videos as the primary method of instruction. The term xMOOC is being used, sometimes pejoratively, to describe these highly structured, one-way courses, with little student interaction (Ross, Sinclair, Knox, Bayne & Macleod, 2014). Such courses are unlikely to help students become comfortable with expressing their views in an academic environment.

Taylor's study is heavily dependent on McCroskey's 1977 idea of communication apprehension (CA) as "... an individual's level of fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons." However this concept was conceived in terms of oral communication in a face-to-face classroom and it is not clear if the theory is directly applicable to a text based CMC. The study also depends on the text contributions to the CMC as a measure of the student's involvement in a course. There is no consideration of other forms of on-line participation, such as via social media, audio, or video.

Taylor suggested that the variability in instructional style of the moderators and the personalities of the participants may explain the lack of correlation between students confidence in communication and their frequency and quantity of forum postings (1998, p. 84). However, the PRCA-24 questionnaire used was designed to measure how confident the students were with communication and no analysis was made of the moderators.

One aspect not adequately addressed in the report was the effect of the course assessment scheme and tutor input on student participation. Taylor comments that "Most moderators allotted a percentage of the final course mark to the conference contributions, ranging from 10 to 20% ... Some required a minimum of 2 contributions per unit ..." (1998, p. 44). The allocation of marks to conference contributions could be expected to have a significant effect on student behaviour, but is not addressed further in the report. Also the practice of allocating marks for student participation does not appear to have been at the discretion of the individual moderators, as Taylor suggests. The official published course descriptions for the period of the research include a set proportion of marks for conference contributions (Athabasca University, 1997). Assuming each moderator carried out the assessment set down for the course, there would be an incentive for students to participate.

Conclusions of The Study

Taylor found that students are reasonably self aware of their level of how much they contribute to forums in a course. But no systematic relationship between oral communication apprehension and levels of computer conference participation was found. While the quantitative analysis of the data has been carried out with the appropriate statistical tools, the qualitative analysis of free form answerers by students appears to be very limited. More analysis of what students said might have yielded better insights that the negative statistical tests show. The results as they stand would apply to the current courses offered in the Athabasca University Master of Education (Distance Education) as the courses, content, teaching methods and assessment to not appear to have changed greatly between 1998 and 2014.

Implications for future research: Perhaps worryingly, this study still has implications for future research more than a decade later. Universities are still grappling with the issue of why some students do not interact online.

An updated version of the communication apprehension questionnaire might be carried out for both students and moderators in relatively conventional online courses (such as those run by Athabasca University), on xMOOCs (large scale course with minimal student interaction) and with courses which encourage students to interact via social media. The nature of interaction for e-learning courses and how it can be supported with software, is yet to be adequately explored (Worthington, 2013).

Conclusion

Taylor found that are reasonably self aware of their level of how much they contribute to forums in a course. But no systematic relationship between oral communication apprehension and levels of computer conference participation was found. The study raises important questions about the role of the human tutor in an online course: what skills should they have and how much freedom to use an individual approach to teaching should they have and what effect this has on student's learning. This has implications beyond individual courses, for universities and educational systems. As an example, the Australian National University(ANU) and the University of Southern Queensland (USQ) formed an "alliance" in 2010 to "... to share teaching, research and enrolment prospects." (Australian National University, 2010). In theory the strengths of the two institutions should complement each other, ANU for research and USQ for online distance education. However, the results of the alliance have been limited, with ANU listing only six USQ courses for their students, of the more than one thousand offered by USQ (Australian National University, 2014). One reason for this may be the differences in the amounts and modes of student interaction for courses of the two institutions. USQ has online courses very similar in format to those of Athabasca University, as studies by Taylor. With such courses the student interaction is within carefully prescribed bounds. The ANU follows a very different approach, where the format, delivery methods and assessment is decided by the lecturer in change, each time a course is run and may be changed while the course is being run. In this environment the student interaction may range from none, to recasting the content and assessment.

Taylor did not find a correlation between a student's communication apprehension (CA) and interaction in a course. However, such a study repeated in a course which has a significant number of students for whom the language of instruction is not their first language, may show different results. In particular, Australian universities are having to accommodate large numbers of students for whom English is a second language and are therefore less confident in communicating in student forums (Worthington, 2012, p. 3). One solution proposed to this problem is to have mixed bilingual classes where English speaking students learning a second language interact on-line with students who speak that language and are learning English (Worthington, 2014, p. 3). Taylor's techniques might be used to assess the success of this approach. One approach which was not available to Taylor in 1998, but can now be applied is measuring reading comprehension by tracking eye movements (Copeland & Gedeon, 2013). This may provide a way to apply the concept of Taylor's analysis routinely, on a much larger scale, for conventional e-learning courses and MOOCs.

References

Athabasca University, (1997, November 7). MDDE 601: Introduction to Distance Education and Training. retrieved July 22 2014, from Course List Web Site: https://web.archive.org/web/19980117111231/http://www.athabascau.ca/html/syllabi/mdde/mdde601.htm

Athabasca University, (2014 May, 27). MDDE 601: Introduction to Distance Education and Training. retrieved July 23 2014, from Athabasca University Web Site: http://cde.athabascau.ca/syllabi/mdde601.php

Australian National University, (2010, February 12). Alliance to forge new directions in higher education. retrieved July 23 2014, from Australian National University Web Site: http://news.anu.edu.au/2010/02/12/alliance-to-forge-new-directions-in-higher-education/

Australian National University, (2014, April 1). University of Southern Queensland online courses. retrieved July 23 2014, from Australian National University Web Site: http://drss.anu.edu.au/gss/usq_online_courses.php

Baxter, J. A., & Haycock, J. (2014). Roles and student identities in online large course forums: Implications for practice. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 15(1). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1593/2763

Breslow, L., Pritchard, D. E., DeBoer, J., Stump, G. S., Ho, A. D., & Seaton, D. T. (2013). Studying learning in the worldwide classroom: Research into edX's first MOOC. Research & Practice in Assessment, 8, 13-25. Retrieved from http://www.rpajournal.com/dev/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/SF2.pdf

Carroll, J. A., Diaz, A., Meiklejohn, J., Newcomb, M., & Adkins, B. (2013). Collaboration and competition on a wiki: The praxis of online social learning to improve academic writing and research in under-graduate students. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 29(4). Retrieved from http://ascilite.org.au/ajet/submission/index.php/AJET/article/download/154/607

Copeland, L., & Gedeon, T. (2013, December). Measuring reading comprehension using eye movements. In Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), 2013 IEEE 4th International Conference on (pp. 791-796). IEEE. Retrieved from http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpls/icp.jsp?arnumber=6719207

Feenberg, A. (1989). The written world: On the theory and practice of computer conferencing. Mindweave: Communication, computers, and distance education, 22-39. Retrieved from http://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/books/The_Written_World_old.pdf

McCroskey, J. C. (n.d.). Personal Report of Communication Apprehension (PRCA-24). retrieved July 22 2014, from Dr. James C. McCroskey Web Site: http://www.jamescmccroskey.com/measures/prca24.htm

McCROSKEY, J. C. (1977). ORAL COMMUNICATION APPREHENSION: A SUMMARY OF RECENT THEORY AND RESEARCH. Human Communication Research, 4(1), 78. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1977.tb00599.x Retrieved from http://www.jamescmccroskey.com/publications/074.pdf

McCroskey, J. C. (1981). Oral Communication Apprehension: Reconceptualization and a New Look at Measurement. Retrieved from http://www.jamescmccroskey.com/publications/101.pdf

McDowell, E. E. (1994). An Exploratory Study of PRCA-24 Variables, Receiver Apprehension (RA) and Telephone Apprehension (TA) for College Students from Australia and the United States. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED379693.pdf

Ross, J., Sinclair, C., Knox, J., Bayne, S., & Macleod, H. (2014). Teacher experiences and academic identity: The missing components of MOOC pedagogy. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 10(1), 56-68. Retrieved from https://oerknowledgecloud.org/sites/oerknowledgecloud.org/files/ross_0314.pdf

Taylor, D. O. (1998). Participation and non-participation in computer mediated conferencing : a case study / by Daniel O. Taylor. --. 1998. Retrieved from http://auspace.athabascau.ca/bitstream/2149/563/1/taylor.pdf

Whitmer, J., Schiorring, E., & James, P. (2014, March). Patterns of persistence: what engages students in a remedial english writing MOOC?. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Learning Analytics And Knowledge (pp. 279-280). ACM. Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2567601

Worthington, T. (2012, July). A Green computing professional education course online: Designing and delivering a course in ICT sustainability using Internet and eBooks. In Computer Science & Education (ICCSE), 2012 7th International Conference on (pp. 263-266). IEEE. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/9013/1/Worthington_Green2012.pdf

Worthington, T. (2013, April). Synchronizing asynchronous learning-Combining synchronous and asynchronous techniques. In Computer Science & Education (ICCSE), 2013 8th International Conference on (pp. 618-621). IEEE. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICCSE.2013.6553983

Worthington, T. (2014). Chinese and Australian students learning to work together online. In Computer Science & Education (ICCSE), 2014 9th International Conference on. IEEE. Advance online publication. http://hdl.handle.net/1885/11724

Theory of Practice

Introduction

This paper presents a personal Theory of Practice for my online teaching to postgraduate students, in vocationally orientated courses (Worthington, 2012). Three learning principles, inspired by Zen maxims of the Martial Arts, are presented: Economy of effort, Realism, and Switching smoothly between techniques. Theory and research literature, are presented to justify these.

Three Learning Principles

Bruce Lee established the Jeet Kune Do system of martial arts in 1967 (Lee, 1975). As with other such systems, this contains elements of an eastern philosophy of life, as well as physical training techniques. Khoo & Senna-Fernandes (2014) sought to use this as inspiration for techniques in plastic surgery, so it does not seem too far-fetched to look to the same source for insights into teaching.

Economy of effort for maximum results

Meditation, Created by Jens Tärning from the Noun Project, CC-BY 3.0, 2014

"One of the greatest adjustments the novice athlete must make in competition is to overcome the natural tendency to try too hard - to hurry, strain, press and try to blast the whole fight at once." (Lee, 1975, p. 57)

Martial arts emphasize maximum results from minimum effort. Similarly, learning is a means to an end and so should be done efficiently: using just enough resources to get the job done. However, most theories of education ignore the cost of an activity. There tends to be an inappropriate emphasis on trying in education, rather than succeeding.

I seek economy of effort in my teaching and try to instill this approach in my students. Courses are aligned with external job skills requirements, with readings and exercises to help the student meet that requirement. But economy of effort is not the same as leaving students to fend for themselves. Kirschner, Sweller and Clark (2006) reviewed studies which showed that lower aptitude students achieved lower results when provided with no, or less, guidance.

Mayer (1999) suggests highlighting the most important information for the leaner using simple techniques (such as bold italics), provide a summary and eliminate irrelevant information. They suggest using the SIO (Select, Organize, Integrate) principles for textbooks and lectures as well as multimedia materials. The techniques of Cognitive Information Processing can be used to provide meaningful structure to the material, with a default sequence (even if the students are encouraged to find their own path). Huang and Andrade (2014, p. 300) suggest methods to manage the cognitive load placed on the student by being able to present only the information the student needs on a mobile device.

Realism

Martial Arts, by Heywood (Public Domain)

"... most systems of martial art accumulate a ' fancy mess'' that distorts and cramps their practitioners and distracts them from the actual reality of combat, which is simple and direct." (Lee, 1975, p. 14)

Education needs to provide the student with useful skills. Students will need to start with simplified exercises, but need to be exposed to increasingly realistic problems. My students either have jobs or are training for a specific role as a professional, their studies are therefore focused on obtaining skills for that job. By providing student exercises which are based on their own workplace, or a reasonable simulation of the workplace, the students are motivated and learn useful skills.

Baviskar, Hartle and Whitney (2009) point out that Constructivism is a theory of learning, not of teaching, but any method of teaching should be based on how students learn. Baviskar, Hartle and Whitney (2009) list the four features of constructivism as: eliciting prior knowledge, creating cognitive dissonance, application of new knowledge with feedback, and reflection on learning

There is an obvious correspondence between these features of learning and the teacher's role in motivating the student with: "... providing content and resources, posing relevant problems and questions at appropriate times..." (Baviskar, Hartle & Whitney, 2009).

Switching smoothly between techniques

Flexible, Created by Borengasser for the Noun Project, CC-BY 3.0 2012

"If nothing within you stays rigid, outward things will disclose themselves. Moving, be like water. Still, be like a mirror. Respond like an echo." (Lee, 1975, p. 5)

Educational literature is full of explanations of why one principle, theory or technique is superior to another. But one approach will rarely do for all situations. Educators need to move smoothly from one technique to another. Students will need times when they learn alone and then others in a group. They can learn the basics using a simple drill and practice computer program (based on behaviorism theory) and then explore advanced topics with other students.

Kanuka and Anderson (1999) claim that competition and student expectations is pressuring higher education institutions to remove time, place, and situational barriers. However, universities seem to have been able to resist that pressure with most students still attending face-to-face classes on campus. They argue that computer mediated conferencing allows for "small group discussions, Socratic dialogue, collaborative/cooperative learning, brainstorming, debriefing, case studies, problem based learning", but simply translating these classroom techniques the online environment is unlikely to significantly increase efficiency. What might make a difference is to be able to blend techniques.

Kanuka and Anderson (1999) create a two dimensional space with a social axis, from socially to individually (the scale would more naturally run the other way from individually to socially) and an axis from subject to objective reality. They then place four forms of constructivism into four quadrants of this space: Cognitive (Individual & Objective), Radical (Individual & Subjective), Situated ( Social & Subjective and Co-Constructivism (Social & Objective).

Kanuka and Anderson (1999) describe and then dismiss each form of Constructivism, until they reach the last, Co-Constructivism, which emphasizes the shared social interaction between students and teacher. This must be comforting for teachers used to the classroom and who can see a path to adopt the same approach on-line. However, the on-line environment provides a way to interact with a large fluid group of people, unlike the small fixed class. Also the many voices challenge the idea that there is an objective reality. When anyone can create a plausible looking web site and edit the Wikipedia, how do you know what is an authoritative source and what is not? All four forms of Constructivism should be able to be applied on-line in one course simultaneously.

One interesting approach is with what Mayer (1999) calls "multi-frame illustrations" with "coordinated captions". These are essentially a cartoon strip, with a series of frames showing a series of steps, with the text on each frame. This was shown to be superior to illustrations with text separate and illustrations on separate pages. Also animation was found to be superior. In my own work I will tend to use simple diagrams and pictograms (Figs. 1 to 3), to highlight points. Babaian and Chalian (2014) report on the use of the narrative techniques of graphic novels for teaching surgery and Meyers (2014) has used comics for teaching Communication Theory. This approach is supported by the Cognitive Information Processing, which encourages the use of graphic representations of information (Huang and Andrade, 2014, p. 300).

Koh, Basawapatna, Nickerson, and Repenning (2014) report using online assessment of computer coding skills using a "Project First, just-in-time" pedagogy, combining Csíkszentmihá¡lyi's Flow (2014) with Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development. In practice this presents the students with a combination of increasingly advanced programming concepts within the same project and more complex projects. The authors claim to be able to track the progress with the student's progress in real time by mining data from the learning management system. However, this level of monitoring might detract from the social aspects of learning and the authors may be stretching these theories beyond breaking point by attempting to implement them explicitly in software. For example Vygotsky (1977, p. 16) referred to the zone of proximal development in relation to children's play and "voluntary intentions" rather than a form of programmed step by step instruction.

Conclusion

Three learning principles, as part of my personal Theory of Practice for online distance teaching are: Economy of effort for maximum results, Realism, and Switching smoothly between techniques. These are intended for teaching computing to postgraduate students on-line and are inspired by the Jeet Kune Do System of Martial Arts. No one approach or technique will be sufficient for all teaching and the practitioner must be ready to apply approaches as required. Learning materials and assessment should be based on real world scenarios and, where possible, incorporate the student's own experience. The cost of teaching and learning, to the teacher and the student, should be taken into account, so resources are used sparingly.

References

Babaian, C. S., & Chalian, A. A. (2014). "The Thyroidectomy Story": Comic Books, Graphic Novels, and the Novel Approach to Teaching Head and Neck Surgery Through the Genre of the Comic Book. Journal of surgical education, 71(3), 413-418. DOI: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.11.008

Baviskar, S. N., Hartle, R. T. & Whitney, T. (2009). Essential criteria to characterize constructivist teaching: Derived from a review of the literature and applied to five constructivist-teaching methods articles. International Journal of Science Education, 31(4), 541 - 550. DOI: 10.1080/09500690701731121

Borengasser, S. (image designer). (2012).Flexible [Pictogram], Noun Project. Retrieved from http://thenounproject.com/term/flexible/43170/

Clark R.E. (1989). When teaching kills learning: research on

mathematics in Mandl H et al (eds) Learning and Instruction Vol 2.2 Pergamon Press,

Oxford/New York, 1-22. Cognition and Technology Group

Huang, W. D., & Andrade, J. (2014). Design and Evaluation of Mobile Learning from the Perspective of Cognitive Load Management. Handbook of Research on Education and Technology in a Changing Society, 291.

Heywood, L (image designer). (2012).Martial-Arts [Pictogram], Noun Project. URL http://thenounproject.com/term/martial-arts/1924

Kanuka, H., & Anderson, T. (1999). Using Constructivism in Technology-Mediated Learning: Constructing Order out of the Chaos in the Literature. Radical Pedagogy,1(2), 2-39.

Khoo, L. S., & Senna-Fernandes, V. (2014). Applying Bruce Lee's Jeet Kune Do Combat Philosophy in Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery - 7 Principles for Success. Modern Plastic Surgery, 2014. DOI: 10.4236/mps.2014.42005

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J. & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75-86.

Koh, K. H., Basawapatna, A., Nickerson, H., & Repenning, A. (2014, July). Real Time Assessment of Computational Thinking. In Visual Languages and Human-Centric Computing (VL/HCC), 2014 IEEE Symposium on (pp. 49-52). IEEE. DOI: 10.1109/VLHCC.2014.6883021

Lee, Bruce (1975). Tao of jeet kune do. Ohara Publications, Santa Clarita, California. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/pdfy-SP1dBDr6xLGrVfF9

Mayer, R. E. (1999). Designing instruction for constructivist learning. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional design theories and models: A new paradigm of instructional theory (pp. 50-67). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Meyers, E. A. (2014). Theory, Technology, and Creative Practice: Using Pixton Comics to Teach Communication Theory. Communication Teacher, 28(1), 32-38. DOI: 10.1080/17404622.2013.839051

Tärning, J. (image designer). (2014).Meditation [Pictogram], Noun Project. URL http://thenounproject.com/term/meditation/51613/

Vygotsky, L. S. (1977). Play and its role in the mental development of the child. (C. Mulholland, Trans.). Soviet developmental psychology, 76-99. Retrieved from http://www.mathcs.duq.edu/~packer/Courses/Psy225/Classic%203%20Vygotsky.pdf

Worthington, T. (2012, July). A Green computing professional education course online: Designing and delivering a course in ICT sustainability using Internet and eBooks. In Computer Science & Education (ICCSE), 2012 7th International Conference on (pp. 263-266). IEEE. DOI: 10.1109/ICCSE.2012.6295070

Needs Assessment and Proposal Development

Introduction

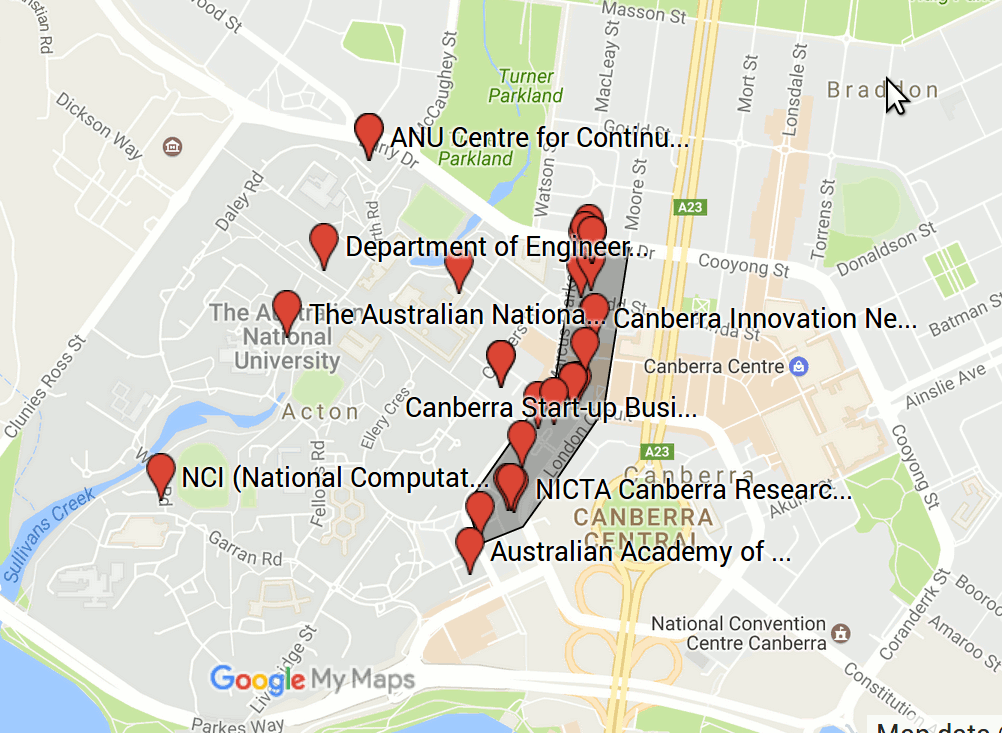

In this chapter I carry out the first two steps in instructional design (ID) for creating a new course provisionally titled "Innovation, Commercialisation and Entrepreneurship in Technology" to be offered on-line, initially for students in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), Canberra. First a needs assessment will be carried out, followed by a proposal for what is to be developed. These first two phases will be fowled in a separate document with creation of one of the learning objects for the course.

An "Innovation ACT" competition was established at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra in 2008 (Blackhall, n.d.). The competition, now supported by the University of Canberra and the local Canberra government (the "ACT Government"), has the aim of providing):

"Entrepreneurial education via seminar sessions ran parallel to a university semester

Entrepreneurial experiences within a competition environment that allows students to test their ideas."

From Innovation ACT (2014a), emphasis added.

The Innovation ACT competition provides students with handbooks and templates, students attend presentations, prepare their proposals with the help of a mentor and then pitch their ideas to a panel of judges (InnovationACT, 2014b). Prasad (2014) discusses the history and educational role of such enterprise competitions and categorizes it as an "action learning" pedagogy.

While popular with students and having an educational role, the Innovation ACT competition is not part of a formal educational program and so is not evaluated as to its educational effectiveness and students do not receive credit for participation towards their studies. This document discusses how to design an on-line course which students could take in conjunction with Innovation ACT and similar competitions, as part of a university degree program. The course would be designed to fit with postgraduate certificate and degree programs in the computing discipline, as that is to author's discipline area.

Kakouris (2009, p. 231) argues for an ADDIE model (Anallise, Design, Develop, Implement and Evaluate) is suitable for providing on-line entrepreneurial education, emphasizing guidance, communication and peer support. They argue that the DE teaching material can be used to implement Gagné's Nine Events of Instruction: Gain Attention, Inform Learners of Objectives, Stimulate Recall of Prior Learning, Present the Content, Provide Learning Guidance, Elicit Performance (Practice), Provide Feedback, Assess Performance, Enhance Retention and Transfer to job" (Gagné (1965) cited in Kakouris (2009, p. 233)).

Is a Human Tutor Needed?

Kakouris (2009, p. 233) assert that the DE system can act as a "virtual educator" without a human tutor. More recently replacing the tutor with an automated system has been attempted with a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) on entrepreneurship. Al-Atabi and DeBoer (2014) report on an entrepreneurship MOOC conducted with 1600 online student in 115 countries, plus 60 on-campus students. The online students formed teams and under took group projects. In addition to videos, the students received points from peers and badges to provide them with feedback on progress. Al-Atabi and DeBoer (2014) noted that the completion rate for online students was 25%, which is higher than a typical MOOC, but was far lower than the 90% completion rate for the students undertaking the same course on-campus.

Neck, Greene and Brush (2014) point out the role for the instructor to "facilitate engagement in creative processes" for higher level skills. As the course under development here is intended to be part of a conventional university degree program, a completion rate of 25% is unacceptably low. It is therefore proposed to take a middle path, having on-line materials, but facilitated by a human tutor, to achieve a completion rate comparable to face-to-face courses.

Part 1: Needs Assessment

Needs assessment approach

Smith and Ragan, (2005, pp. 43) suggest that an ID needs assessment should first establish if there is a need at all. They outline a cycle of needs assessment, design, production, implementation and evaluation (Smith and Ragan, 2005, pp. 44), while advocating the evaluation plans actually be constructed during the needs assessment phase. This may be unrealistic where the need for a course has not yet been established and so work on evaluation would be wasted if the course is never run.

Smith and Ragan, (2005, pp. 44) divided needs assessments into three model types:

-

Problem Model: As Smith and Ragan note, it is necessary to determine if there really is a "problem" and if a cause it the best way to solve it. In the case of an unsolicited new course on innovation, the problem model is not as applicable, as there is no current group of employees to canvas. As the aim is to have students go out and create new companies, there are also not employers to consult. The Innovation ACT competition is part funded by the local government, which has in an economic development strategy to foster new industries, a "culture of entrepreneurship" and encourage startup firms to provide employment (ACT Government 2013). The ACT Government might therefore be consulted about the problem of educating innovators.

-

Innovation Model: This approach looks for changes in the students, the education system or the environment. The innovation model would seem apt for a course in innovation: students are less likely to want to simply get a job in a corporation and instead want to set up their own company. The approach of involving students in an innovation competition working on a real world project is not new in the Australian education system (along with e-learning and e-portfolio systems which make it easier to offer such education), but not widely used. However, the reduction in the available of jobs for life has required graduates to be more entrepreneurial, being able to take on new roles and even invent a job for themselves. Thompson and Kwong (2013) found that "enterprise education", designed to develop entrepreneurial skills, in UK schools had a "direct positive relationship with entrepreneurial activities and intentions". This indicates that students will respond positively to such education and an introductory course on innovation with lead to the student doing more such work.

-

Discrepancy Model: The discrepancy model, as described by Smith and Ragan, (2005, pp. 45) , does not start with a new need, but as a check to see if an existing course is meeting the already established requirements. This applies to an innovation course, as some such courses already exist, along with externally set skills requirements. The analysis to be carried out therefore incorporates some elements of the discrepancy model, at least to say what is wrong with existing courses and so why a new course is required. With this the requirements will be listed and how well these are met with courses, to determine the gap.

Scope and extent of the need

a. Who to query. As there is a question over the popularity of the existing course, the first group to survey are potential students. It would be simpler to have access to students currently enrolled in a program of study (as they are easy to access). But it may be worthwhile contacting those who have not been attracted to programs, perhaps via a professional body, such as the Australian Computer Society and Engineers Australia. These bodies could also asked as to the need. Innovation organizations, such as the various "co-working" offices and "hacker" competition providers may be of use. In addition experts in the field can be consulted, as Dr. Lachlan Blackhall, founder of Innovation ACT (Blackhall, n.d.), who has worked on engaging students with real world problems (Smith, Brown, Blackhall, Loden & O'Shea, 2010).

b. How to Query. An on-line survey instrument could be used to collect information from potential students. This could use multiple choice and rating questions. Interviews could be used with organizational representatives. However, they are unlikely to agree to a formal social science style of interview and a more informal approach may need to be used.

c. Type of questions. Reimers-Hild and King, (2009) proposed six questions for entrepreneurial leadership and innovation in the context of distance education. These could be applied more generally for questioning potential students and employers about innovation courses:

-

"How entrepreneurial is your organization? On a scale of 1-5, would you classify your organization as a 1 (not at all entrepreneurial) or a 5 (extremely entrepreneurial)?

-

How are administrators, instructors and learners in your organization learning to be more entrepreneurial?

-

Developing a global mindset throughout an organization characterized by risk taking, innovation and change should be encouraged, not discouraged. ...

-

Is innovation a priority? On a scale of 1-5, would you classify your organization as a 1 (not at all innovative) or a 5 (extremely innovative)?...

-

In what ways can your leaders share the vision ... Can they use both face-to-face and online methods? Can they use both individual and large group settings?...

-

How can you institutions connect employees and learners with their passions and their personal vision of the future?...

-

What is your organization doing to develop and leverage the human and social capital of its administrators, instructors and students? ..."

From Reimers-Hild and King , 2009 (emphasis added) .

d. Other data sources. While the sources discussed above may be of some use, the primary source of information will be preexisting skills definitions and syllabuses. In particular Australian computer science degrees are accredited by the Australian Computer Society (ACS, 2014). The Society promotes the use of an internationally standardized skills framework and courses are required to be "aligned" with the framework (IP3, 2015). It would therefore be appropriate to based the course on the most appropriate skills definitions in that framework. McEwan (2013) discusses the use of SFIA skills definitions (SFIA Foundation Ltd, 2015) for university courses and note it is particularly useful for fast developing new job categories (SFIA is also part of the ACS/IP3 framework). McEwan proposed the use of SFIA level 5/6 for Masters-level courses and 4/5 for Honors-level. They also found that one SFIA skill was insufficient for a typical university course and used two. In this case McEwan (2013) aligned a course with skills "Emerging Technology Monitoring" (EMRG) and "Innovation" (INOV).

Alongside the university system, Australia has a system of Vocational Education and Training (VET), which as Mazzarol (2014) points out, has been active in offering courses in entrepreneurship for small business. Some universities have associated VET Registered Training Organizations (RTOs) to deliver such courses, at a lower qualification level than their degree programs.